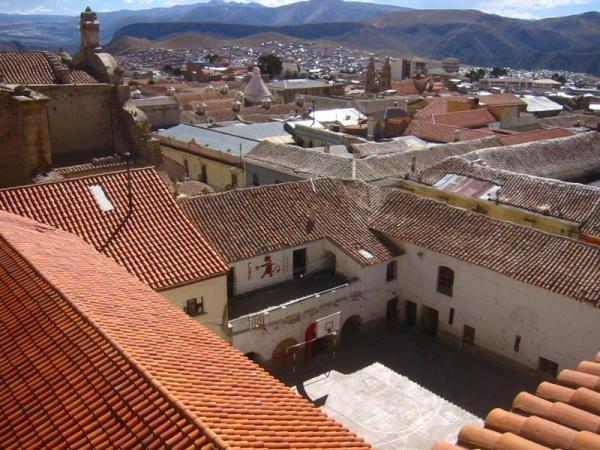

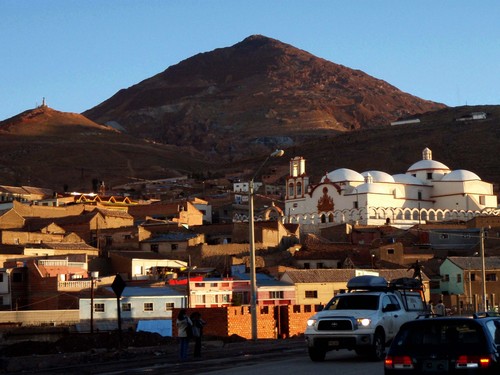

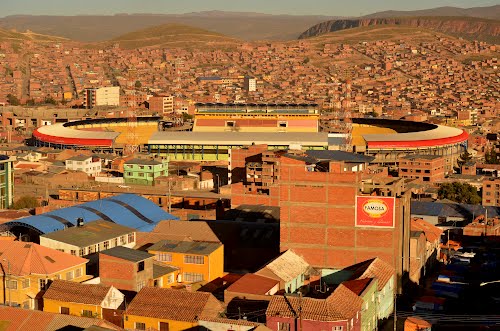

Potosi is a city and the capital of the department of Potosi in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world by elevation at a nominal 4,090 metres. For centuries, it was the location of the Spanish colonial mint.

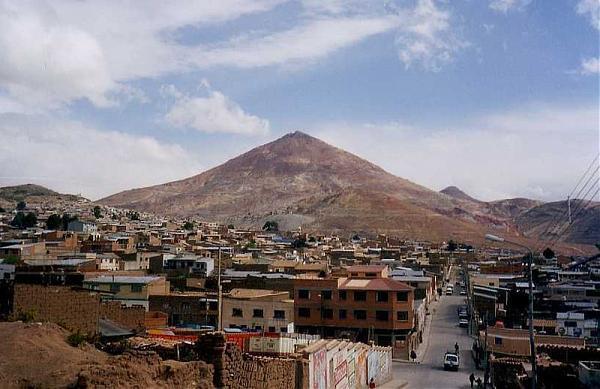

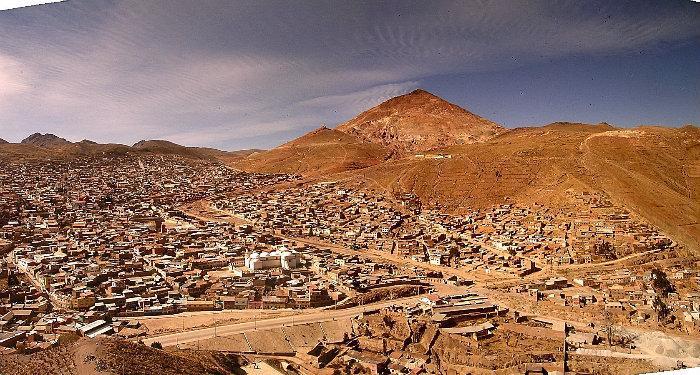

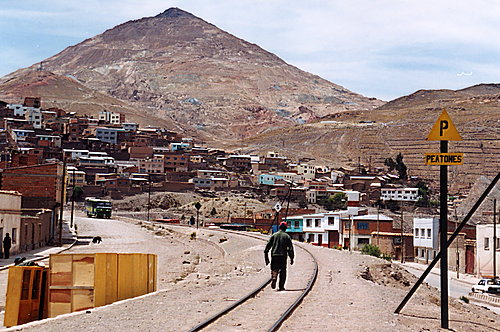

Potosi lies at the foot of the Cerro de Potosi - sometimes referred to as the Cerro Rico, a mountain popularly conceived of as being "made of" silver ore that dominates the city. The Cerro Rico is the reason for Potosí's historical importance, since it was the major supply of silver for Spain during the period of the New World Spanish Empire.

The silver was taken by llama and mule train to the Pacific coast, shipped north to Panama City, carried by mule train across the isthmus of Panama to Nombre de Dios or Portobelo whence it was taken to Spain on the Spanish treasure fleets.

Cerro de Potosi's peak is 4,824 metres above sea level.

History and silver extraction

16th century silver boom

Founded in 1545 as a mining town, it soon produced fabulous wealth, and the population eventually exceeded 200,000 people. The city gave rise to a Spanish expression, still in use: vale un Potosi, meaning "to be of great value". The rich mountain, Cerro Rico, produced an estimated 60% of all silver mined in the world during the second half of the 16th century.

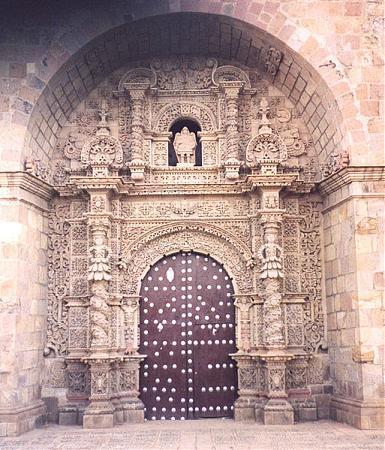

Potosi's naturally rich deposits, along with technological advancements in production like the Patio process, allowed silver production costs to remain extremely low. In fact, Spanish American mines were the world's cheapest sources of silver during this time period. Spanish America's ability to supply a great amount of silver and China's strong demand for this commodity resulted in a spectacular mining boom. The true champion of this boom in the silver industry was indeed the Spanish crown. By allowing private-sector entrepreneurs to operate mines and placing high taxes on mining profits, the Spanish empire was able to extract the greatest benefits. From the raw materials extracted from the mines, the Potosi mint called pieces of eight were fashioned.

For Europeans, Peru–Bolivia was part of the Viceroyalty of Peru and was known as Alto Peru before becoming independent as part of Bolivia. Potosi was a mythical land of riches, it is mentioned in Miguel de Cervantes' famous novel, Don Quixote as a land of "extraordinary richness". One theory holds that the mint mark of Potosi (the letters "PTSI" superimposed on one another) is the origin of the dollar sign, although the likelier origin of the symbol is the $ - shaped scroll-wrapped columns on the reverse of the Spanish dollar.

Forced labor

Native-American laborers were conscripted and forced to work in Potosi's silver mines through the traditional Incan mita system of contributed labor. Many of them died due to the harsh conditions of the mine life. At such a high altitude, pneumonia was always a concern and mercury poisoning took the lives of many involved in the refining process.

From around 1600, the death rate skyrocketed among the local Indian communities. To compensate for the diminishing indigenous labor force, the colonists made a request in 1608 to the Crown in Madrid to begin allowing the importation of 1,500 to 2,000 African slaves per year. An estimated total of 30,000 African slaves were taken to Potosi during the colonial era. Like the native laborers, they too died in large numbers. African slaves were also forced to work in the Casa de la Moneda (mint) as acémilas humanas (human mules). Since mules would die after a couple of months pushing the mills, the colonists replaced the four mules with twenty African slaves.

Independence era

During the Bolivian War of Independence (1809–1825), Potosi frequently passed between the control of Royalist and Patriot forces. Major leadership mistakes came when the First Auxiliary Army arrived from Buenos Aires (under the command of Juan Jose Castelli), this led to an increased sense that Potosi required its own independent government.

When the second auxiliary army arrived, it was received well and the commander, Manuel Belgrano, did much to heal the past wounds inflicted by the tyrannical Castelli. When that army was forced to retreat, Belgrano took the calculated decision to blow up the Casa de la Moneda. Since the locals refused to evacuate, the explosion would have resulted in many casualties. The fuse was lit, but disaster was averted by locals who put the fuse out. Two more expeditions from Buenos Aires would seize Potosi.