Tiwanaku is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia.

The site was first recorded in written history by Spanish conquistador Pedro Cieza de Leon. He came upon the remains of Tiwanaku in 1549 while searching for the Inca capital Qullasuyu.

The name by which Tiwanaku was known to its inhabitants may have been lost as they had no written language. The Puquina language has been pointed out as the most likely language of the ancient inhabitants of Tiwanaku.

Structures

The area around Tiwanaku may have been inhabited as early as 1500 BC as a small agricultural village. During the time period between 300 BC and AD 300, Tiwanaku is thought to have been a moral and cosmological center for the Tiwanaku empire to which many people made pilgrimages. Researchers believe it achieved this standing prior to expanding its powerful empire.

The structures that have been excavated at Tiwanaku include the Akapana, Akapana East, and Pumapunku stepped platforms, the Kalasasaya, the Kheri Kala, and Putuni enclosures, and the Semi-Subterranean Temple. These may be visited by the public.

The Akapana is an approximately cross-shaped pyramidal structure that is 257 m wide, 197 m broad at its maximum, and 16.5 m tall. At its center appears to have been a sunken court. This was nearly destroyed by a deep looters excavation that extends from the center of this structure to its eastern side. Material from the looters excavation was dumped off the eastern side of the Akapana. A staircase with sculptures is present on its western side. Possible residential complexes might have occupied both the northeast and southeast corners of this structure.

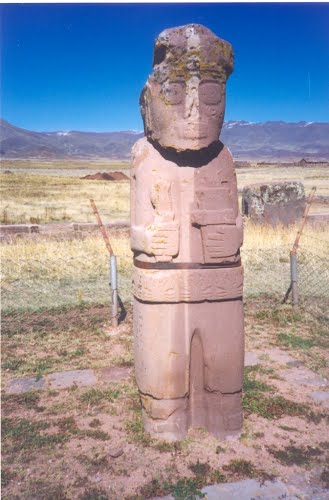

Originally, the Akapana was thought to have been made from a modified hill. Twenty-first century studies have shown that it is a manmade earthen mound, faced with a mixture of large and small stone blocks. The dirt comprising Akapana appears to have been excavated from the "moat" that surrounds the site. The largest stone block within the Akapana, made of andesite, is estimated to weigh 65.70 metric tons. The structure was possibly for the shaman-puma relationship or transformation through shape shifting. Tenon puma and human heads stud the upper terraces.

The Akapana East was built on the eastern side of early Tiwanaku. Later it was considered a boundary between the ceremonial center and the urban area. It was made of a thick, prepared floor of sand and clay, which supported a group of buildings. Yellow and red clay were used in different areas for what seems like aesthetic purposes. It was swept clean of all domestic refuse, signaling its great importance to the culture.

The Pumapunku is a man-made platform built on an east-west axis like the Akapana. It is a rectangular terraced earthen mound faced with megalithic blocks. It is 167.36 m wide along its north-south axis and 116.7 m broad along its east-west axis, and is 5 m tall. Identical 20-meter wide projections extend 27.6 meters north and south from the northeast and southeast corners of the Pumapunku. Walled and unwalled courts and an esplanade are associated with this structure.

A prominent feature of the Pumapunku is a large stone terrace; it is 6.75 by 38.72 meters in dimension and paved with large stone blocks. It is called the "Plataforma Litica". The Plataforma Lítica contains the largest stone block found in the Tiwanaku Site. Ponce Sangines the block is estimated to weigh 131 metric tons. The second largest stone block found within the Pumapunku is estimated to be 85 metric tons.

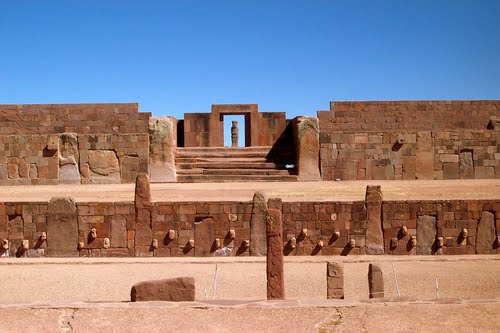

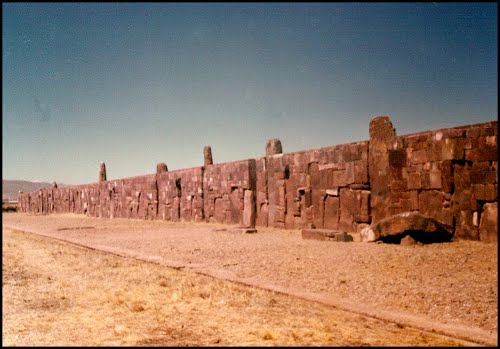

The Kalasasaya is a large courtyard over three hundred feet long, outlined by a high gateway. It is located to the north of the Akapana and west of the Semi-Subterranean Temple. Within the courtyard is where explorers found the Gateway of the Sun. Since the late 20th century, researchers have theorized that this was not the gateway's original location. Near the courtyard is the Semi-Subterranean Temple, a square sunken courtyard that is unique for its north-south rather than east-west axis. The walls are covered with tenon heads of many different styles, suggesting that the structure was reused for different purposes over time. It was built with walls of sandstone pillars and smaller blocks of Ashlar masonry. The largest stone block in the Kalasasaya is estimated to weigh 26.95 metric tons.

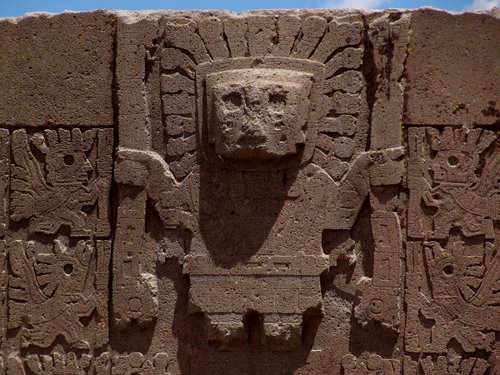

Within many of the site's structures are impressive gateways, the ones of monumental scale are placed on artificial mounds, platforms, or sunken courts. Many gateways show iconography of "Staffed Gods." This iconography also is used on some oversized vessels, indicating an importance to the culture. This iconography is most present on the Gateway of the Sun.

The Gateway of the Sun and others located at Pumapunku are not complete. They are missing part of a typical recessed frame known as a chambranle, which typically have sockets for clamps to support later additions. These architectural examples, as well as the recently discovered Akapana Gate, have a unique detail and demonstrate high skill in stone-cutting. This reveals a knowledge of descriptive geometry. The regularity of elements suggest they are part of a system of proportions.

Many theories for the skill of Tiwanaku's architectural construction have been proposed. One is that they used a luk’a, which is a standard measurement of about sixty centimeters. Another argument is for the Pythagorean Ratio. This idea calls for right triangles at a ratio of five to four to three used in the gateways to measure all parts. Lastly Protzen and Nair argue that Tiwanaku had a system set for individual elements dependent on context and composition. This is shown in the construction of similar gateways ranging from diminutive to monumental size, proving that scaling factors did not affect proportion. With each added element, the individual pieces were shifted to fit together.

As the population grew, occupational niches developed, and people began to specialize in certain skills. There was an increase in artisans, who worked in pottery, jewelry and textiles. Like the later Incas, the Tiwanaku had few commercial or market institutions. Instead, the culture relied on elite redistribution. That is, the elites of the empire controlled essentially all economic output, but were expected to provide each commoner with all the resources needed to perform his or her function. Selected occupations include agriculturists, herders, pastoralists, etc. Such separation of occupations was accompanied by hierarchichal stratification within the empire.

The elites of Tiwanaku lived inside four walls that were surrounded by a moat. This moat, some believe, was to create the image of a sacred island. Inside the walls were many images devoted to human origin, which only the elites would see. Commoners may have only entered this structure for ceremonial purposes since it was home to the holiest of shrines.