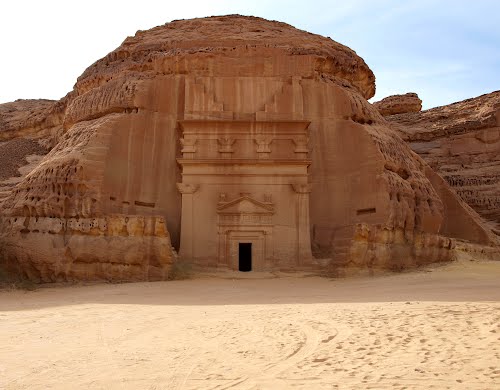

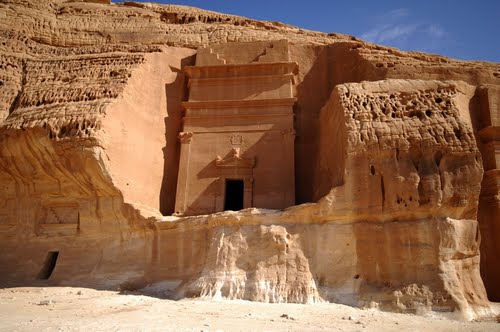

Mada'in Saleh, also called Al-Hijr or Hegra, is an archaeological site located in Province of Al-Madinah in the Region of the Hejaz, Saudi Arabia. A majority of the vestiges date from the Nabatean kingdom (1st century AD). The site constitutes the kingdom's southernmost and largest settlement after Petra, its capital. Traces of Lihyanite and Roman occupation before and after the Nabatean rule, respectively, can also be found.

The Qur’an places settlement of the area by the Thamudi people during the days of Saleh, between those of Noah and Moses. According to the Islamic text, the Thamudis, who carved out homes in the mountains, were punished by Allah for their practice of idol worship, being struck by an earthquake and lightning blasts. Thus, the site has earned a reputation as a cursed place - an image which the national government is attempting to overcome as it seeks to develop Mada'in Saleh for its potential for tourism.

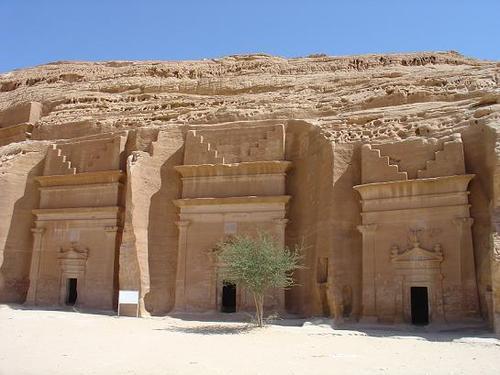

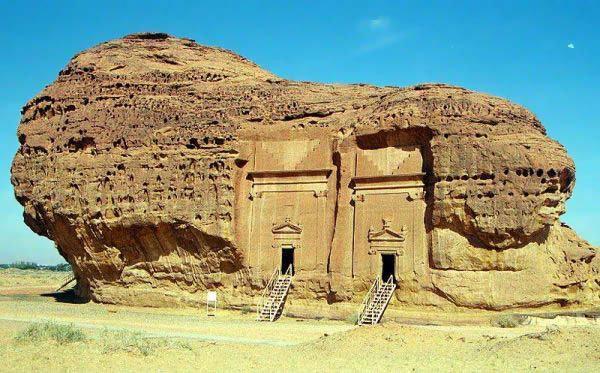

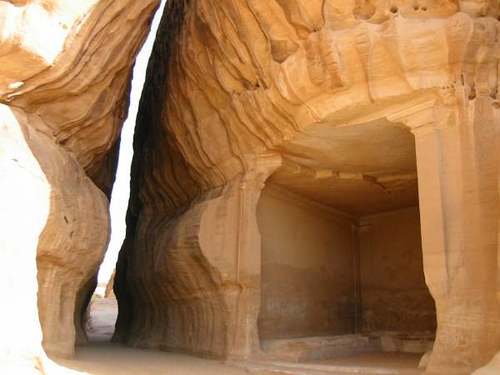

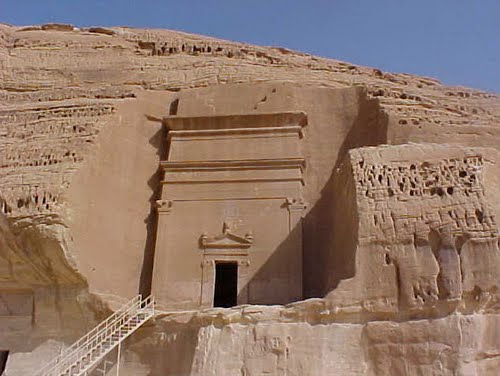

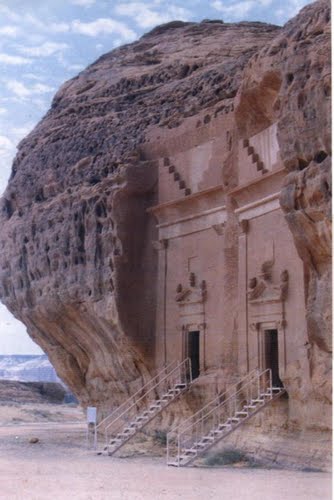

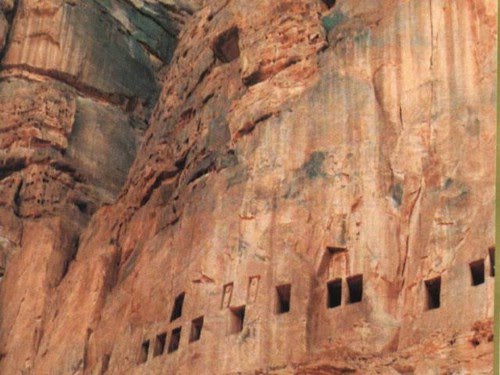

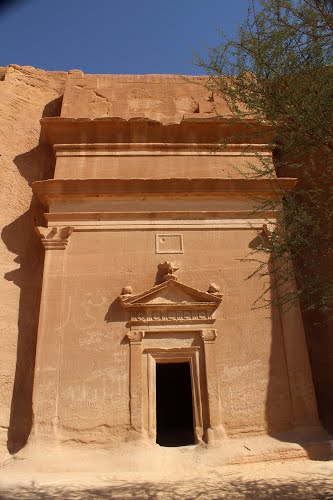

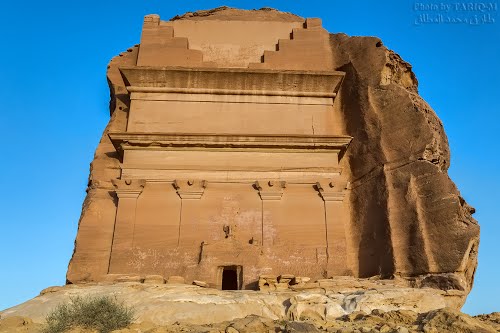

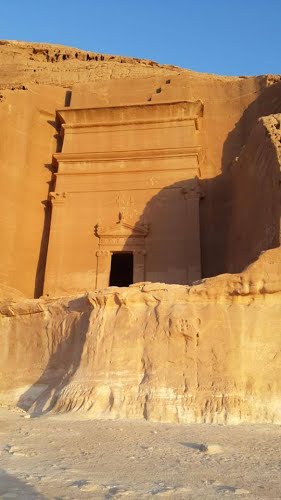

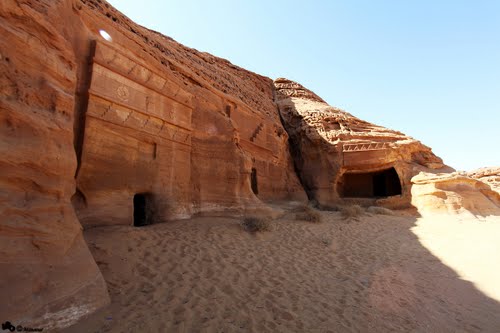

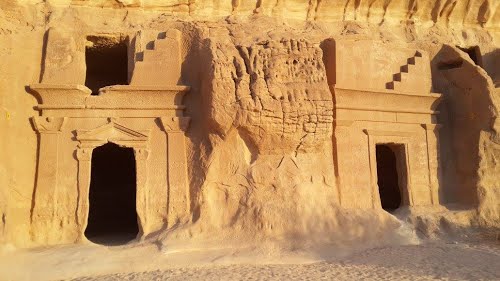

In 2008 UNESCO proclaimed Mada'in Saleh as a site of patrimony, becoming Saudi Arabia's first World Heritage Site. It was chosen for its well-preserved remains from late antiquity, especially the 131 rock-cut monumental tombs, with their elaborately ornamented façades, of the Nabatean kingdom.

History

Era of Salih

According to Islamic Tradition, by the 3rd millennium BC, the site of Mada'in Salih had already been settled by the tribe of Thamud.It is said that the tribe fell to idol worship, and oppression became prevalent. Salih, to whom the site's name of Mada'in Salih is often attributed, called the Thamudis to repent. The Thamudis disregarded the warning and instead commanded Saleh to summon a pregnant she-camel from the back of a mountain. And so, a pregnant she-camel was sent to the people from the back of the mountain by Allah, as proof of Saleh's divine mission. However, only a minority heeded his words. The non-believers killed the sacred camel instead of caring for it as they were told, and its calf ran back to the mountain where it had come from, screaming. The Thamudis were given three days before their punishment was to take place, since they disbelieved and did not heed the warning. Saleh and his Monotheistic followers left the city, but the others were punished by Allah - their souls leaving their lifeless bodies in the midst of an earthquake and lightning blasts.

The Lihyans

Lihyan is an ancient Arab kingdom. It was located in Mada'in Saleh, and is known for its Old North Arabian inscriptions dating to ca. the 6th to 4th centuries BC. Dedanite is used for the older phase of the history of this kingdom since their capital was Dedan, now called Al-`Ula, 22 km to the south.

Pre-Nabatean vestiges

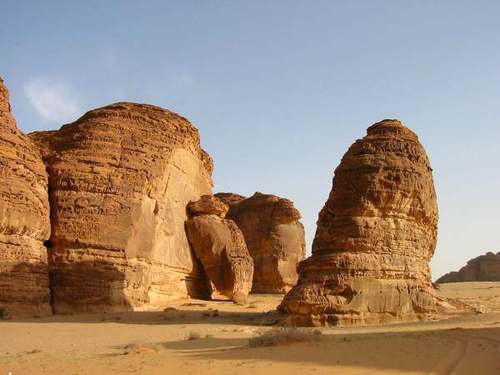

Archaeological traces of cave art on the sandstones and epigraphic inscriptions, considered by experts to be Lihyanite script, on top of the Athleb Mountain, near Mada'in Saleh, have been dated to the 3rd–2nd century BC, indicating the early human settlement of the area, which has an accessible source of freshwater and fertile soil. The settlement of the lihyans became a center of commerce, with goods from the east, north and south converging in the locality.

Nabatean settlements

The extensive settlement of the site took place during the 1st century AD, when it came under the rule of the Nabatean king Al-Harith IV (9 BC –40 AD), who made Mada'in Saleh the kingdom's second capital, after Petra in the north. The place enjoyed a huge urbanization movement, turning it into a city. Characteristic of Nabatean rock-cut architecture, the geology of Mada'in Saleh provided the perfect medium for the carving of monumental and settlements, with Nabatean scripts inscribed on their façades. The Nabateans also developed oasis agriculture - digging wells and rainwater tanks in the rock and carving places of worship in the sandstone outcrops. Similar structures were featured in other Nabatean settlements, ranging from southern Syria to the north, going south to the Negev, and down to the immediate area of Hejaz. The most prominent and the largest of these is Petra.

At the crossroad of commerce, the Nabatean kingdom flourished, holding a monopoly for the trade of incense, myrrh and spices. Situated on the overland caravan route and connected to the Red Sea port of Egra Kome, Mada'in Saleh, then referred to as Hegra among the Nabateans, reached its peak as the major staging post on the main north–south trade route.

Roman era

In 106 AD, the Nabatean kingdom was annexed by the contemporary Roman Empire. The Hejaz, which encompasses Hegra, became part of the Roman province of Arabia.

The Hedjaz region was integrated into the Roman province of Arabia in 106 AD. A monumental Roman epigraph of 175-177 AD was recently discovered at al-Hijr.

The trading itinerary shifted from the overland north–south axis on the Arabian Peninsula to the maritime route through the Red Sea. Thus, Hegra as a center of trade began to decline, leading to its abandonment. Supported by the lack of later developments based on archaeological studies, experts have hypothesized that the site had lost all of its urban functions beginning in the late Antiquity. Recently evidence has been discovered that the Roman legions of Trajan occupied Madain Salih in the Hijaz mountains' area of northeastern Arabia, increasing the extension of the "Arabia Petraea" province of the Romans in Arabia.

The history of Hegra, from the decline of the Roman Empire until the emergence of Islam in the days of Muhammad, remains unknown. It was only sporadically mentioned by travelers and pilgrims making their way to Mecca in the succeeding centuries. Hegra served as a station along the Hajj route, providing supplies and water for pilgrims.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman Empire annexed western Arabia from the Mamluks by 1517. In early Ottoman accounts of the Hajj road between Damascus and Mecca, Mada'in Saleh is not mentioned, until 1672. Between 1744 and 1757,[5][18] a fort was built at al-Hijr on the orders of the Ottoman governor of Damascus, As'ad Pasha al-Azm. A cistern supplied by a large well within the fort was also built, and the site served as a one-day stop for Hajj pilgrims where they could purchase goods such as dates, lemons and oranges. It was part of a series of fortifications built to protect the pilgrimage route to Mecca.

19th Century

Following the discovery of Petra by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812, Charles Montagu Doughty, an English traveler, heard of a similar site near Mada'in Saleh, a fortified Ottoman town on the Hajj road from Damascus. In order to access the site, Doughty joined the Hajj caravan, and reached the site of the ruins in 1876, recording the visit in his journal which was published as Travels in Arabia Deserta. Doughty described the Ottoman fort, where he resided for two months, and noted that Bedouin tribesmen had a permanent encampment just outside of the building.

In the 19th Century, there were accounts that the extant wells and oasis agriculture of al-Hijr were being periodically used by settlers from the nearby village of Tayma. This continued until the 20th century, when the Hejaz Railway that passed through the site was constructed (1901–08) on the orders of Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II to link Damascus and Jerusalem in the north-west with Medina and Mecca, hence facilitating the pilgrimage journey to the latter and to politically and economically consolidate the Ottoman administration of the centers of Islamic faith. A station was built north of al-Hijr for the maintenance of locomotives, and offices and dormitories for railroad staff. The railway provided greater accessibility to the site. However, this was destroyed in a local revolt during World War I. Despite this, several archaeological investigations continued to be conducted in the site beginning in the World War I period to the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the 1930s up to the 1960s. The railway station has also been restored and now includes 16 buildings and several pieces of rolling stock.

By the end of the 1960s, the Saudi Arabian government devised a program to introduce a sedentary lifestyle to the nomadic Bedouin tribes inhabiting the area. It was proposed that they settle down on al-Hijr, re-using the already existent wells and agricultural features of the site. However, the official identification of al-Hijr as an archaeological site in 1972 led to the resettlement of the Bedouins towards the north, beyond the site boundary. This also included the development of new agricultural land and freshly dug wells, thereby preserving the state of al-Hijr.