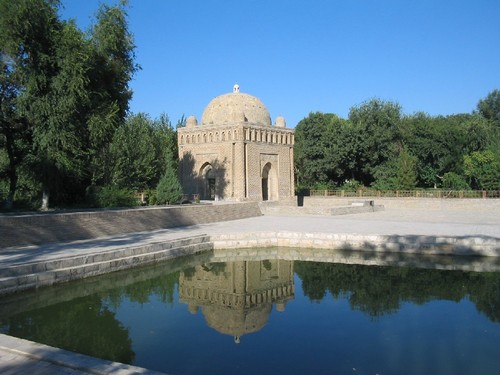

The Samanid mausoleum is located in a park just outside the historic urban center of Bukhara, Uzbekistan. The mausoleum is considered to be one of the most highly esteemed work of Central Asian architecture, and was built between 892 and 943 A.D as the resting-place of Ismail Samani - a powerful and influential amir of the Samanid dynasty, one of the last native Persian dynasties that ruled in Central Asia in the 9th and 10th centuries, after the Samanids established virtual independence from the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. In addition to Ismail Samani, the mausoleum also houses the remains of his father Ahmed and his nephew Nasr, as well as the remains of other members of the Samanid dynasty.

Significance

The fact that the religious law of orthodox Sunni Islam strictly prohibits the construction of mausoleums over burial places stresses the significance of the Samanid mausoleum, which is the most ancient monument of Islamic architecture in Central Asia and the sole monument that survived from the epoch of the Samanid Dynasty. The Samanid mausoleum might be one of the earliest departures from that orthodox religious restriction in the history of Islamic architecture.

The shrine is regarded as one of the oldest monuments in the Bukhara region - at the time of Genghis Khan's invasion, the shrine was said to have already been buried in mud from flooding. Thus, when the Mongol hordes reached Bukhara, the shrine was spared from their destruction. The site was only rediscovered in 1934 by Soviet archeologist V.A. Shishkin, and required two years for excavation.

The shrine has been considered sacred by local residents, and pilgrims would pose dilemmas and questions to a mullah who would reply from behind a wall in order to preserve anonymity for petitioners. The shrine was once the centerpiece of a vast cemetery where even the former Emirs of Bukhara were buried.

During the Soviet era, the local cemetery was paved over, and an amusement park was built immediately adjacent to the shrine which is still in operation. A park was also built to completely surround the shrine.

Architecture

The monument marks a new era in the development of Central Asian architecture, which was revived after the Arab conquest of the region. The architects continued to use an ancient tradition of baked brick construction, but to a much higher standard than had been seen before. The site is unique for its architectural style which combines both Zoroastrian motifs from the native Sogdian and Sassanid cultures, as well as Islamic motifs introduced from Arabia and Persia.

The building's facade is covered in intricately decorated brick work, which features circular patterns reminiscent of the sun - a common image in Zoroastrian art from the region at that time which is reminiscent of the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda, who is typically represented by fire and light. The building's shape is cuboid, and reminiscent of the Ka'aba in Makkah, while the heavy corner buttresses are derived from Sogdian architectural styles. The syncretic style of the shrine is reflective of the 9th and 10th centuries - a time when the region still had large populations of Zoroastrians who had begun to convert to Islam around that time.

The height of the shrine is approximately 35 feet, with four identically designed facades which gently slope inwards with increasing height. The building's architectural engineers included four internal arches for support, upon which the dome is placed. The building's "four arch" design was adopted for use in several shrines throughout Central Asia. At the top of each side of the shrine are ten small windows which provided ventilation for the interior portion of the mausoleum.