The Battle of the Neva was fought between the Novgorod Republic and Karelians against Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish and Tavastian armies on the Neva River, near the settlement of Ust-Izhora, on 15 July 1240. The battle is only mentioned in Russian sources, which raises doubts about its significance or even existence.

The purpose of the invasion was probably to gain control over the mouth of the Neva and the city of Ladoga and, hence, seize the most important part of the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, which had been under Novgorod's control for more than a hundred years. The battle was part of the medieval Swedish-Novgorodian Wars and continuum to Finnish-Novgorodian wars.

Russian sources

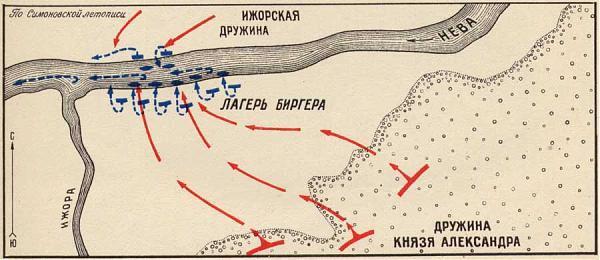

The existence of the battle is only known from Russian sources. The first source to mention the battle is the Novgorod First Chronicle from the 14th century. According to the chronicle, on receiving the news of the advancing Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish and Tavastian fleets, the 20-year-old Prince Alexander Yaroslavich of Novgorod quickly moved his small army and local men to face the enemy before they had reached Lake Ladoga.

A 16th-century version of the battle gave plenty of additional details, expanding the conflict to biblical proportions, but otherwise following the earlier described developments.

Prince Alexander Yaroslavich was nicknamed "Nevsky" for his first significant victory. Two years later, Alexander stalled an invasion of the Livonian Knights during the Battle on the Ice. Despite the victories, there were no Novgorodian advances further west to Finland or Estonia.

Swedish sources

Situation in Sweden

Since the death of King John in 1222, Sweden was in a de facto state of civil war until 1248 when Birger Jarl managed to seize power in the kingdom. Unrest was due to the struggle between those who wanted to keep the old tribal structure, the folkung party, and the king, who was assisted by the church. Folkungs, who were mainly from Uppland, heavily resisted the centralization of power, taxation of the Swedes of Uppland, and church privileges. They had temporarily succeeded in deposing the king in 1229, but were forced to give in five years later, but were far from defeated yet. Uppland remained largely independent of the king, and its northern areas continued to be in folkung hands. An uneasy truce continued until 1247, when the folkung rebellion was put to an end at the Battle of Sparrsatra and its leader beheaded a year later.

Furthermore, the official Sweden was on the brink of war with Norway ever since the Norwegians' infamous Varmland expedition in 1225. Relations improved only after the Treaty of Lodose in 1249, which was forged by the newly empowered Birger Jarl. Before the treaty, Norway remained an ally of the folkungs, giving them refuge and providing men and arms.

In this situation, it seems unlikely that Sweden could have been able to organize a major expedition against Novgorod. Swedes are not known to have carried out any other military campaigns between 1222 and 1249, making the claims about their forceful appearance at the Neva with Norwegians as their allies seem questionable.

Theories

Taking these facts into consideration, it has been suggested in a recent book aimed at a wide readership, that the Swedish expedition may have been an indirect result of the papal letter in 1237 that was sent to the Swedish Archbishop of Uppsala. The letter eloquently called for a crusade, not against Novgorod, but against Tavastians in Finland, who had allegedly started hostilities against the church. In his defunct position, the king may not have been willing or able to act, but the letter may have provided the frustrated folkungs an opportunity to regain part of their Viking Age glory. Mostly free to act without interference from the king, folkungs would have been able to raise an army of their own, get volunteers from Norway and even assistance from Thomas, the independent Bishop of Finland, who needed to constantly worry about attacks from the east. Instead of Tavastia, this mixed set of interests and nationalities would have headed for the more lucrative Neva and there met its fate at the hands of Alexander. In the possible aftermath of the said battle, the King of Norway approached his Swedish counterpart for peace talks in 1241, but was turned down at the time.

However, some recent research has fundamentally questioned the importance of the battle, seeing it as an ordinary border skirmish that was exaggerated for political purposes, thus also explaining its absence from Swedish and other western sources.

Additional theories are numerous. Some historians have suggested that the Swedish army was already under the command of the very young Birger Jarl, eight years before his appointment to the position of jarl. It has also been suggested that the suspicious information on Norwegians', Finns' and Tavastians' participation was made up in the 14th century, the time of writing of the First Novgorod Chronicle, when Sweden was in control of Norway, Finland and Tavastia.

Consequences

All in all, the first known Swedish military expedition against Novgorod after the events at the Neva took place in 1256, following folkungs' demise, peace with Norway and conquest of Finland. If the battle of the Neva had any long-term consequences, it was in Sweden's determination to take over Finland first before attempting to proceed further east.