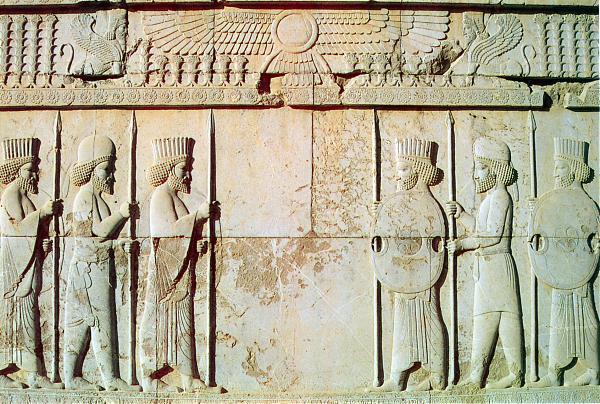

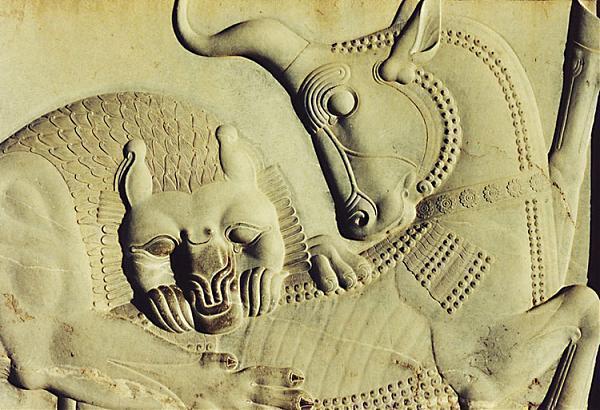

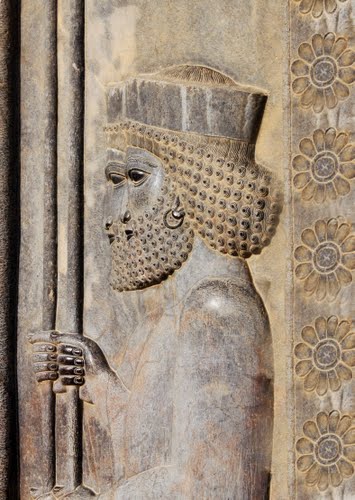

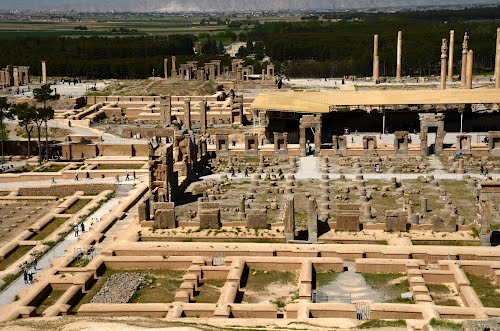

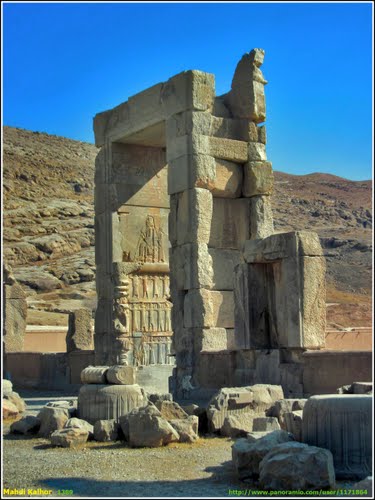

Persepolis, also known as Takht-e-Jamshid, was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550–330 BC).

Persepolis is situated 60 km northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars Province, Iran. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

History

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. Andre Godard, the French archaeologist who excavated Persepolis in the early 1930s, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site of Persepolis, but that it was Darius I who built the terrace and the palaces.

Since, to judge from the inscriptions, the buildings of Persepolis commenced with Darius I, it was probably under this king, with whom the scepter passed to a new branch of the royal house, that Persepolis became the capital of Iran proper. As the residence of the rulers of the empire, however, a remote place in a difficult alpine region was far from convenient. The country's true capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This accounts for the fact that the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until Alexander the Great took and plundered it.

Darius I ordered the construction of the Apadana and the Council Hall, as well as the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings. These were completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings on the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire.

Around 519 BC, construction of a broad stairway was begun. The stairway was initially planned to be the main entrance to the terrace 20 metres above the ground. The dual stairway, known as the Persepolitan Stairway, was built symmetrically on the western side of the Great Wall. The 111 steps measured 6.9 metres wide, with treads of 31 centimetres and rises of 10 centimetres. Originally, the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback. New theories, however, suggest that the shallow risers allowed visiting dignitaries to maintain a regal appearance while ascending. The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the north-eastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of All Nations.

Grey limestone was the main building material used in Persepolis. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, the terrace was prepared. Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated water storage tank was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain. Professor Olmstead suggested the cistern was constructed at the same time that construction of the towers began.

The uneven plan of the terrace, including the foundation, acted like a castle, whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front. Diodorus writes that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, which all had towers to provide a protected space for the defense personnel. The first wall was 7 metres tall, the second, 14 metres and the third wall, which covered all four sides, was 27 metres in height, though no presence of the wall exists in modern times.

Destruction

After invading Achaemenid Persia in 330 BC, Alexander the Great sent the main force of his army to Persepolis by the Royal Road. He stormed the "Persian Gates", a pass through the modern Zagros Mountains, and quickly captured Persepolis before its treasury could be looted. After several months, Alexander allowed his troops to loot Persepolis.

Around that time, a fire burned "the palaces" or "the palace". Scholars agree that this event, described in historic sources, occurred at the ruins that have been now re-identified as Persepolis. From Stolze's investigations, it appears that at least one of these, the castle built by Xerxes I, bears evident traces of having been destroyed by fire. The locality described by Diodorus after Cleitarchus corresponds in important particulars with the historic Persepolis, for example, in being supported by the mountain on the east.

It is believed that the fire which destroyed Persepolis started from Hadish Palace, which was the living quarters of Xerxes I, and spread to the rest of the city. It is not clear if the fire was an accident or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the second Persian invasion of Greece. Many historians argue that while Alexander's army celebrated with a symposium, they decided to take revenge against the Persians.

The Book of Arda Wiraz, a Zoroastrian work composed in the 3rd or 4th century, describes Persepolis' archives as containing "all the Avesta and Zend, written upon prepared cow-skins, and with gold ink," that were destroyed. Indeed, in his Chronology of the Ancient Nations, the native Iranian writer Biruni indicates unavailability of certain native Iranian historiographical sources in post-Achaemenid era, especially during the Arsacid Empire. He adds, "Alexander burned the whole of Persepolis as revenge to the Persians, because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years ago. People say that, even at the present time, the traces of fire are visible in some places."

Paradoxically, the event that caused the destruction of the these texts may have resulted in the preservation of Achaemenid administrative archives, which might otherwise have been lost over time to natural and man-made events. According to archaeological evidence, the partial burning of Persepolis did not affect what are now referred to as the Persepolis Fortification Archive tablets, but rather may have caused the eventual collapse of the upper part of the northern fortification wall that preserved the tablets until their recovery by the Oriental Institute's archaeologists.

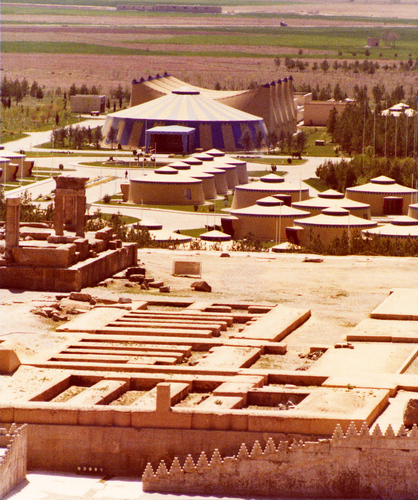

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire

In 316 BC, Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire. The city must have gradually declined in the course of time. The lower city at the foot of imperial city might have survived for a longer time, but the ruins of the Achaemenids remained as a witness to its ancient glory. It is probable that the principal town of the country, or at least of the district, was always in this neighborhood.

About 200 BC, the city of Estakhr, five kilometers north of Persepolis, was the seat of the local governors. From there, the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and there Estakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sassanid kings have covered the face of the rocks in this neighborhood, and in part even the Achaemenid ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions. They must themselves have been built largely there, although never on the same scale of magnificence as their ancient predecessors. The Romans knew as little about Estakhr as the Greeks had known about Persepolis, despite the fact that the Sassanids maintained relations for four hundred years, friendly or hostile, with the empire.

At the time of the Muslim invasion of Persia, Estakhr offered a desperate resistance. It was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis of Shiraz. In the 10th century, Estakhr dwindled to insignificance, as seen from the descriptions of Estakhri, a native (c. 950), and of Mukaddasi (c. 985). During the following centuries, Estakhr gradually declined, until it ceased to exist as a city.